|

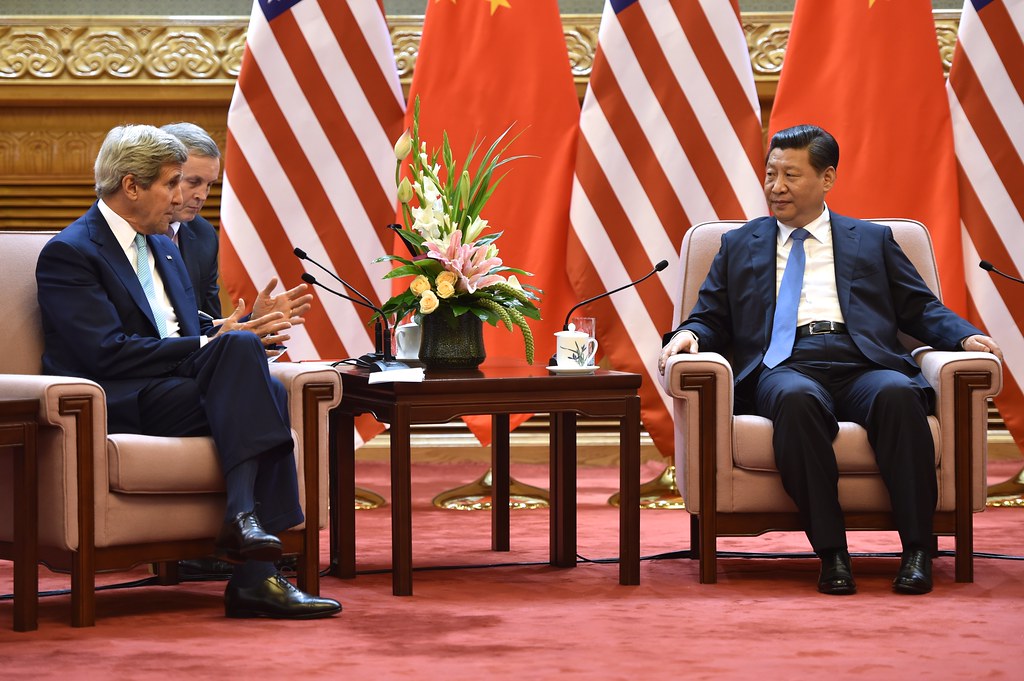

| Image: Flickr User - U.S. Department of State |

By Mercy A. Kuo and Angelica O. Tang

Insight from Tom Kane

The Rebalance authors Mercy Kuo and Angie Tang regularly engage subject-matter experts, policy practitioners and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into the U.S. rebalance to Asia. This conversation with Dr. Tom Kane – Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Security Studies, University of Hull, United Kingdom and author of numerous publications, including Strategy: Key Thinkers, Understanding Contemporary Strategy, and Chinese Grand Strategy and Maritime Power, among others – is the 26th in “The Rebalance Insight Series.”

What are the core elements of Chinese grand strategy and how have they evolved from the ancient period to the present day?

The founder of China’s Zhou Dynasty established the principle that his country should be a large state defined by its cultural ideals. Although China has split up at numerous points throughout its history, its leaders have consistently returned to this principle. They hold to it today. Moreover, as China has come into contact with powerful outsiders, Chinese leaders have become increasingly aware that, for their country to thrive as an independent state, they need to take full advantage of its geographical position and economic capabilities. These are the core elements of China’s grand strategy, and the government of the People’s Republic appears to be carrying out a successful long-term program of responding to them.

The most widely recognized parts of this program have been the economic reforms of the 1980s, and Beijing’s subsequent attempts to achieve national prosperity. As the PRC’s growing role in international trade has made it more influential, it has displayed an increasing willingness to engage with international organizations, and to lobby within them for its own interests. The PRC has also used its wealth to modernize its armed forces. Although its military capabilities remain modest when compared, for instance, to those of the United States, Beijing appears to be borrowing another concept from Chinese tradition and practicing the “empty fortress” tactic of using assertive behavior to achieve a reputation for power. Since neither China nor its potential opponents wish to escalate their disputes to actual war, this reputation often becomes reality – a concept examined in my Parameters analysis on China’s power projection capabilities.

Read the full story at The Diplomat